Photo 1

Photo 1

Amate tree bark produced the dark coffee and creamy beige colors (L and C), and mulberry bark produced the silvery beige-gray (R).

As Americans travel the world and purchase art from around the globe the corner frame shop and gallery is faced with many types of art they may not have ever seen before. It's one thing to read an article about thangkas or Bo Leaf paintings, it's another issue when one is brought in to be framed. These are not traditional oil paintings, acrylics or watercolors, but other collectables like Mexican amate bark, and Egyptian papyrus, or Tahitian tapa cloth paintings.

Identification First

As with framing any art, correct identification of the project is the first stage of design, known as definition ("Essence of Design", PFM February 2000). In the case of painted art, knowing both the media and the substrate greatly helps in best determining how to mount and frame that art. If the media is waterproof such as oils or acrylics then the art may be left unglazed. If the paint in question is egg tempera or watercolor it must be protected with acrylic or glass. Not all shiny pigments are oils or acrylics and not all dull, matte finish, flat pigments are tempera. European watercolors are translucent by nature, but an opaque watercolor called gouache is not, and gouache looks very much like tempera. The substrate must also be understood in order to know whether mounting or stretching would be best.

Amate Bark

Amate bark from Mexico is made by the Otomi Indians from the Amate or Jonote tree, Mulberry tree or Xalama Limon. The bark of the tree selected determines the color of the paper: Amate is a dark coffee color; Mulberry is silvery beige; and Xalama is white, while all carry a very unique texture and mottled surface (photo 1). Amate paper is dominantly used to create cut out figures for Otomi religious ceremonies, but sheets are also sold to artisans for paintings that depict pastoral scenes, festivals and celebrations. Generally very inexpensive, low quality paints are used for painting these and all art should be glazed (photo 2).

Photo 1

Photo 1

Amate tree bark produced the dark coffee and creamy beige colors (L and C), and mulberry bark produced the silvery beige-gray (R).

Photo 2

Photo 2

The paints used on this sample of coffee colored amate park is probably an egg tempera. Though lightfast it is water soluble and requires glass.

Tapa Cloth

Tapa, or tapa cloth, is also made of bark but it originates from the islands in the South Pacific, including Tonga, Samoa, New Guinea and Hawaii. Called tapa in Tahiti; saipo in Samoa; and kapa in Hawaii, it has been traditionally used for clothing. Today it is used mostly for painting and special ceremonial dress. Sheets are made by stripping outer bark from inner bark of the tree, then the inner bark is dried in the sun prior to soaking. It is then beaten by hand into thin strips, which are placed at perpendicular directions to each other and beaten together into a sheet, not unlike papyrus paper (photo 3).

Photo 3

Photo 3

This sample of papyrus paper clearly illustrates the cross hatched placement of bark strips that have been beaten together to create a sheet for painting. This is the format used for both tapa and papyrus.

Painted patterns form grided squares of repetitive geometrical motifs and are colored with traditional dyes of black and rust-brown. Unlike the surface painting on the above amate bark, tapa patterns are imprinted on the surface of the sheet by means of placing a raised carved pattern behind it. Colored dye is then rubbed onto the tapa surface picking up the textured pattern placed beneath it, like a stone rubbing. Though the finished image is relatively durable the sheets will lose strength and fall apart if wet. Hinging would be best for these, glazing might be optional.

Papyrus

Along the same line of beaten tapa, is papyrus. Our current word paper derived from the word papyrus, though it is nothing like it. Paper is produced from individual fibers screen sieved to make a full sheet, while papyrus is made by pounding together narrowly cut strips from the stalk of the Cyprus Papyrus plant.

After the stalks are split, soaked and become pliable, they are cross-hatched to form sheets which are placed between two hard absorbent barriers and pressed to dry in the sun. Every 8 hours the absorbent layers are replaced for 3 or 4 days until all the strips are thoroughly dry. The dry papyri sheets are then used for paintings, letters and recording events using oils, gouache, or ink (photo 4).

Photo 4

Photo 4

Dry papyri sheets are used for paintings using oil pigments, opaque gouache, or ink. This sample looks and smells like gouache.

Although ancient papyri may be pressed between sheets of glass for museum presentation and storage, it is ill-advised for a framer to do likewise. For old, brittle or fragmented sheets, Mylar or acrylic glazing may create too much static and could increase potential fiber damage. Contemporary paintings are easily obtained and in most cases inexpensive tourist art that may be floated or matted using Japanese hinges, edge strips or corners (photo 5).

Photo 5

Photo 5

Contemporary paintings are often uneven at the edges or out of square as seen in this sample. They may be floated or matted using Japanese hinges, edge strips or corner pockets.

Mulberry Paper

A surface commonly used for painting in Asia besides silk, is mulberry paper ("Making Mulberry Paper", PFM June, 2005). Though Chinese papers are made dominantly from mulberry bark fibers, other common fibers include rice, bamboo, and kapok. These other fibers are often added to expand upon the properties of the basic paper fibers such as adding strength, weight, or texture. Papers which create more interesting textures are frequently made from linen and hemp (photo 6).

Photo 6

Photo 6

Heavyweight rice paper like this sample has a toothy surface and the perfect absorbency. Notice the tiny flecks of bark remaining in the paper surface.

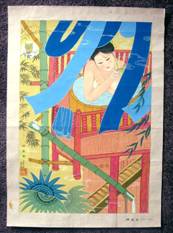

Asian artists love mulberry papers because of their toothy surface and perfect absorbency level for gouache (photo 7). The featured fine art painting by Mr. Liao from Kaili, China was painted as a 53cm x36cm (14 x21") image on a sheet of 17 x24" heavyweight, handmade rice paper (photo 8). Since most Asian pigments are inks or watercolors the paper substrate must handle paint moisture and have a desirable surface tooth for painting. Even on heavyweight papers the pigments may soak well into the paper surface and nearly bleed through to the back (photo 9).

Photo 7

Photo 7

Matte finish opaque watercolors called gouache are often the pigment of choice. These are Marie's Gouache manufactured in Beijing, China and used by most village artists.

Photo 8

Photo 8

This fine art painting by Mr. Liao from Kaili, China was painted as a 53 x36cm (14 x21") image on a sheet of 17 x24" heavyweight handmade rice paper using gouache.

Photo 9

Photo 9

Notice the ghosting of the pigment saturating into, almost through the mulberry paper. Adhesives will saturate as well and may alter the original pigment colors.

Care should be taken when mounting fine art such as this because of high moisture absorption. Hinges and corner pockets should be considered first over dry or wet mounting for these. Soaked adhesives could easily saturate into the paper as the paint did and alter the original pigment colors on the face of the art.

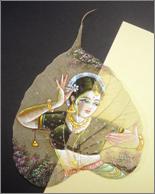

Sacred Fig Leaf

Another natural substrate popular for painting is the leaf from the Ficus religiosa, a fig tree which is also part of the Mulberry family. Common names for this tree include Bodhi, Bo, Pipal (peepal), Ashwattha and Sacred Fig Tree. It is considered a scared tree in Hinduism and Buddhism because it is said Buddha sat and meditated under it searching for enlightenment. The tree is native to India, southwest China, and Indochina to Vietnam.

The leaves are used as a substrate and are often painted on depicting mythical stories, rural village scenes, or religious themes (photo 10). They are often attached to a backing and covered with tissue to protect them from damage during storage, sale or general handling. The leaves are large, about the size of a hand, and somewhat spade shaped with a long tail. They are quite delicate and lacy (photo 11).

Photo 10

Photo 10

They are often used as a painting substrate depicting mythical or religious themes.

These two have been glued by their stem to a black backing and covered with glassine to protect them from damage.

Photo 11

Photo 11

The leaves are large, about the size of a hand, and somewhat spade shaped with a long tail.

They are quite delicate, lacy and may easily be seen through.

Framing Painted Art

Once the painted art in question has been identified as to the media and the material it has been painted onto, then deciding how to creatively frame it while respecting it's uniqueness is the next design stage know as creativity. When framing a Sacred Bo leaf there are a few options, but the two most obvious are to leave it mounted to it's thin backing or remove it from that backing and remount it.

Removal from Backing

If removal and remounting is chosen then the leaf must first be carefully removed from the backing (photo 12). It has been glued in a few spots along the central stem and will need to be separated with extreme care. The leaf is supple yet delicately brittle and may easily split or tear. Since the paint is not known it may not be safe to use water to attempt to soften the adhesive to release the leaf from its backing. Aggressively pulling it may easily damage the leaf. A small ½" tear occurred towards the pointed end of the leaf during this removal by pulling the leaf from the backing by grasping only the larger stem end (photo 13).

Photo 12

Photo 12

If removal and remounting is chosen then the leaf must first be carefully removed from it backing.

It has been glued in a few spots along the central stem and will need to be separated.

Photo 13

Photo 13

The leaf is soft and supple yet delicately brittle and may easily tear during removal.

A ½" tear towards the pointed end of the leaf occurred during this removal.

It is always much safer to remove the backing from the leaf by laying the leaf face down on a soft surface and pulling the disposable backing from it, supporting the stem as you go. Once removed from the backing the few glue spots may easily be seen when the leaf is laying face down (photo 14). These may or may not be easy to remove and perhaps leaving the slight bits of residue is the best solution. When the removed Bo leaf is turned face up it is time to select the appropriate framing materials to best enhance and protect this art. It was most likely purchased on a trip to India or Indonesia and though may not have a high monetary or intrinsic value will no doubt be emotionally valuable to your customer.

Photo 14

Photo 14

The black glue spots that held it in place may easily be seen once the leaf has been removed and is laying face down.

These may or may not be easy to remove and perhaps leaving the slight bits of residue is the best solution.

Color and Texture

Since the leaf is lacy and may be seen through the choice of backing color and texture will be very important to the final frame design. Selecting a dark, probably black, background will best showcase the delicacy of the leaf and keep the painted colors from washing out by color ghosting. When the leaf is placed over black matboard the colors stay crisp and the leaf is easily outlined. When placed over a creme matboard the light color bleeds through and washes out the painting (photo 15). Once black becomes the chosen color then assorted other issues come into play. What shade of black? Should it have a texture or be smooth? And, how will it be attached to the new backing?

Photo 15

Photo 15

The left half is placed over a black matboard while the right half is placed over crème mat board which bleeds through and washes out the painting.

All blacks are not created equal. There are warm blacks and cool blacks. Lightfast colors and those that will fade away by visible light even with UV glazing. The four blacks selected for consideration were Columbe: a 400# handmade, pigmented, lightfast, rough and knobby textured paper from Spain; Sennelier Pastel Paper: a 300# handmade pigmented, lightfast, medium textured toothy surfaced cool black paper from France; Bainbridge #8663 AlphaRag, pigmented, relatively lightfast, 4ply mat board; and 60# Strathmore acid free, machine made, charcoal paper, pigmented, lightfast, lightly textured. All were pigmented, neutral pH, lightfast, high quality papers (photo 16).

Photo 16

Photo 16

Test the leaf over assorted black backgrounds checking for color and texture tolerance. (left to right) Columbe heavily textured handmade paper; Sennelier Pastel Paper with toothy but smooth surface and cooler black color; Bainbridge #8663 AlphaRag 4ply mat board, smooth surfaced; and Strathmore AF Charcoal paper, lightweight with laid line texture.

Final Frame

The chosen paper backing for this project was the beautifully knobby Columbe Spanish handmade paper. The leaf was spot mounted to the paper with Lineco neutral pH adhesive using a toothpick, and was matted with a deep bevel, fabric wrapped, free form window mat covered with black linen (photo 17). Watch for my June or July article featuring this complete creative mounting project.

Photo 17

Photo 17

The leaf has been spot wet mounted down it's stem to Columbe and matted with a deep bevel, linen wrapped, free form window mat. Stay tuned for the entire creative mounting project later this year.

The problems surrounding the mounting of painted art may be minimized once the media and substrate have been identified. Your customer may help you by knowing what they have and where it was acquired. Do not hesitate to ask the questions necessary to do your job...like, "what is this?" Plus in the 21st century we now have the web and researching any project is only a click away.

END

Copyright © 2007 Chris A Paschke

For more articles on mounting basics look under the mounting section in Articles by Subject.

Additional information on all types of mounting is found in:

The Mounting and Laminating Handbook, Second Edition, 2002,

The Mounting And Laminating Handbook, Third Edition, 2008 and

Creative Mounting, Wrapping, And Laminating, 2000 will teach you everything you need to know about getting the most from your dry mount equipment and materials as an innovative frame designer.

All books are available from Designs Ink Publishing through this website.

Chris A Paschke, CPF GCF

Designs Ink

Designs Ink Publishing

785 Tucker Road, Suite G-183

Tehachapi, CA 93561

P 661-821-2188

chris@designsinkart.com