There was a recent discussion on PPFA Hitchhikers email forum over the handling, smoothing out of wrinkles, and mounting of Asian silk papers with possible solutions. Back in February 2000 I wrote an article on wet mounting that touched on the topic of traditional Japanese mounting methods, but I see there is need to delve further into this topic.

During my trip to China last summer I had the opportunity to discuss and observe the basics of traditional scroll mounting techniques first hand. This is an art that takes many years to perfect and should not be attempted without proper training.

West Appreciates East

There has been an increasing appreciation in the West of paintings and calligraphy of East Asia, which has brought us to want more information on their mounting as scrolls. In Japanese houses, a hanging scroll is used as interior decoration just as we use framed art. Occasionally these scrolls may be rolled up, returned to storage, or replaced by another, just as we might reframe something or purchase a new piece of art for our home. The art of the mounting of the displayed scroll is often evaluated and revered along with the painting itself, just as we hope our customers will do with our custom framing.

Apart from aesthetic considerations, the basic technique of scroll mounting is considered fine art conservation. Most deterioration of scrolls, such as creasing and tears in the support, flaking of paint layers, or general lack of flatness, can be corrected and/or restored by remounting. A scroll conservator, or specialist in the conservation of oriental paintings would most likely be a master in this techniques of scroll mounting.

What To Do and When To Do It

The information presented in this two part article is designed to inform you about but not literally to teach you how to mount scrolls. The mounting methods have been highly abbreviated and should never be attempted without extensive specialized training by a master. I hope to introduce, inform, and help educate you so you may better assist customers and travelers who may be bringing into their treasured Asian artifacts and collectibles. As always, the more you know and are able to intellectually discuss a technique or process with your customer the more you prove yourself as a specialized professional. Knowing when NOT to undertake a project is every bit as important as when and how TO tackle one.

Japanese Apprenticeship

In Japan, training to be a mounter is by apprenticeship of ten to fifteen years. Historically, a child of ten years old would be sent to his master's studio to spend the first two to three years watching the master work. In another two to three years he would be permitted to do very simple tasks such as joining backing sheets or cutting paper. Next he could actually back materials then finally mount a piece of art.

Today a mounting student begins to study with a master after completing secondary school, but will still undergo ten years of additional training to me a scroll mounter. Then there remains personal experience, along with that training from the master that will make the student skilled at the art of mounting. Now consider for a moment how much time you might have spent reading, attending classes, or studying with a Western master to learn everything you perhaps need to know about the skills of wet, spray, pressure-sensitive and dry mounting.

Apprenticeship in any art in Japan is rated as in any martial art by ku (color belt) and dan, the higher levels of black belt (first degree black belt, second degree black belt). So, technically a master could hold a third degree black belt in scroll mounting.

Understanding Parts of a Scroll

There are very specific basic parts to a Japanese scroll. The honshi is the main body of art, the calligraphy or painting. The narrow strip of brocade placed immediately above the honshi is the ichimonji-jo, and is usually twice the width of the ichimonji-ge which immediately below the art. The two decorative strips attached to the upper rod (hyomoku) is equal to or slightly wider than the ichimonji-ge, about 1/25th the total width of the scroll itself.

The part between the jo (top of the scroll) and the ichimonji-jo is known as the chu-jo, and that between the ge (bottom of the scroll) and the ichimonji-ge is known as the chu-ge. Together these are called the chu, and are always the same fabric as the hashira to the right and left of the honshi. Jo is the upper part of the scroll and ge is the lower. The fabric often used to decorate this is plain, light colored silk, shadow monochromatic brocade or patterned silk.

The upper rod was traditionally made of bamboo but cedar is often used today. It is flat at the front and semicircular at the back. The lower rod is wrapped with the same material as the ge, is round and usually of Japanese cedar. The Chinese prefer sandalwood because it does not absorb as much moisture as other kinds of wood and helps prevent insect damage. Decorative end knobs are added to the rods and can be made of ivory, lacquer, crystal, animal horn, metal, porcelain, or various kinds of wood.

History and Background

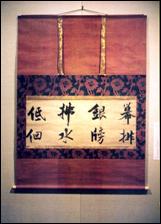

The mounting technique was first introduced into Japan from China in the 6th century. Various techniques developed until the 16th century, by which time it was then established as one of the most important arts. That is when the three basic hanging scroll styles still practiced today were first established, the Shin, Gyo, and So (photo 1) types (diagrams 2, 3 and 4).

Photo 1

Photo 1

This gyo style scroll (diagram 4A) is traditionally used for mounting haiku (Japanese poetry), letters, and paintings of beauties. They may be either horizontal or long verticals. This was taken at the recent Princeton Collection of Chinese Art exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum NY.

Contemporary scrolls from the Hyogu and Mincho styles are less ornamented (diagram 5) by the elimination of upper decorative strips using a more basic approach (photo 2). These samples were from an adult education art class in Beijing, China this past summer.

Photo 2

Photo 2

These contemporary scrolls are from an adult art class in Beijing, China. They showcase the more minimal Hyogu and Mincho style scrolls (diagram 5) without fukuro trims at the top. Left to right scrolls 1 and 4 are based on so style (diagram 4C), while 2, 3, and 5 are hyogu (diagram 5A and 5B).

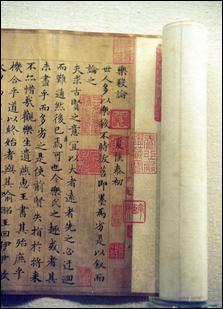

Historically each owner of any scroll or document placed his cinnabar vermilion colored inked seal, also known as a chop, at the beginning and often the end of the scroll (photo 3). This was meant to designate ownership, authority, and the longevity of reference and authenticity of that artwork or document. There are often numerous chops stacked in the margins, on the edged silk, and even infringing upon the art itself.

Photo 3

Photo 3

The addition of each owners seal to the beginning and/or end of a scroll was used to designate ownership, authority, and authenticity of that artwork or document. There are often numerous chops stacked in the margins, on the edged silk, and even infringing upon the art itself. This antique scroll was seen in the Metropolitan Museum, NY.

Style Scrolls: For Formal Presentations

These are the most formal scroll styles called Shin. There are subcategories, but the commonality is the suspended inner image (chuberi) with a completely surrounded outer frame (soberi). These are used for Buddhist paintings, and contain very specific thin white silk strips and plain woven violet (suji) between the larger outer frames for definition and contrast.

Gyo Style Scrolls: The Most Common

The Gyo style is the most common of mountings. The suspended scroll reaches edge to edge and the honshi is surrounded by ichimonji and chuberi frames, with the jo and ge added separately at the top and bottom. This style was used to display colored paintings of birds and flowers, warriors, Imperial autographs, Taoist figures and Buddhist descriptions. Scroll B is the most common contemporary design used dominantly today.

So Scrolls: Informal and Versatile

This So style is an informal mounting in which the hashira is extremely narrow. This is used mostly in ceremonial tea rooms, paintings of beauties, and short one or two line sentences and poems by monks and tea masters. More horizontal designs may also be applied to this format. Photo 1 shows the scroll design in 4A.

Hyogu and Mincho Style Scrolls

Hyogu style scrolls have eliminated the ichimonji and chuberi so the honshi (art) is directly on the soberi. A suji of woven silk is frequently inserted around the edges of the honshi as an accent. Styles A and B are used for mounting landscape paintings, birds and flowers with poetry, all done the the basic Chinese techniques. Photo 4.

Photo 4

Photo 4

Acrylic boxes display antique scrolls in their naturally designed presentation. Met Museum, NY.

The Mincho style (C and D) was popular during the Chinese Ming Dynasty and later in Japan. It showcases a narrow strip of silk along the outer left and right edges from top tp bottom. Futai decorative strips are not used in this style. Style C is used for paintings of landscapes, bamboo and stones, birds and flowers, ink paintings, and Chinese poetry or characters. Style D has broader strips of silk material at the edges with the joge the same width as the honshi. When this occurs suji is often inserted between them. This style is used for mounting narrow, oblong paintings usually of orchids, bamboo and stones, and Sumi paintings. Also for paintings in pairs.

Scroll Calculations

Measurements of the parts of the scroll (diagram 1) are calculated in relation to the honshi (artwork) in order to have the most pleasing proportions. Although current mounters often slightly modify the standards to suit their own tastes, the original standards where set during the Tokugawa period and are best exemplified by the gyo scroll styling shown in diagram 3B.

First the ichimonji-jo is established to be visually most pleasing in comparison to the honshi. Then the chu-jo is 4X (four times) that height, with the jo being 3X (three times) the height of the chu-jo. The ichimonji-ge, chu-ge, and ge were then exactly half of the upper jo dimensions. Today the lower portions may be slightly more than half the upper dimensions. The width of the hashira is slightly less than half the height of the chu-jo, and the width of the futai equals the ichimonji-ge.

The Rest of the Story

Now that the basic concepts have been introduced next month in "Part Two: The Rest Of The Story" I'll introduce and examine the yellow belt version of scroll mounting. Consider yourself a ten year old and be ready to aborb whatever you can, even if it's only to realize this is a form of Karate way over our heads.

END

Copyright © 2001 Chris A Paschke

For more articles on mounting basics look under the mounting section in Articles by Subject.

Additional information on all types of mounting is found in:

The Mounting and Laminating Handbook, Second Edition, 2002,

The Mounting And Laminating Handbook, Third Edition, 2008 and

Creative Mounting, Wrapping, And Laminating, 2000 will teach you everything you need to know about getting the most from your dry mount equipment and materials as an innovative frame designer.

All books are available from Designs Ink Publishing through this website.

Chris A Paschke, CPF GCF

Designs Ink

Designs Ink Publishing

785 Tucker Road, Suite G-183

Tehachapi, CA 93561

P 661-821-2188

chris@designsinkart.com